MAYA CALENDAR AND MESOAMERICAN ASTRONOMY

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MAYA TIME The Mayan communities of present-day Mexico and Central America developed an intricate calendar with origins as early as the eighth century BCE. Though many today first encounter it through tabloid coverage of supposed predictions the calendar makes about the “end” of time, its fame in the history of science rests in part on the technological, social, and political sophistication the calendar reveals was required to reliably track historical time. Ancient Mayan cultures are best known in contemporary popular culture by representations of the archaeological sites of Tikal, Palenque, Copan and Chich’en Itza. Alongside their “pyramid temples” these sites are often recognized for the calendric records found in numerous hieroglyphic inscriptions. And while Mayan communities still thrive and struggle in southern Mexico and Central America, and while the content of the inscriptions is now understood to comprise multiple literary genres, this is likely all overshadowed in modern popular culture by the apocryphal interpretations of the “end of the Mayan calendar” in the year 2012. When we get past these straw man interpretations, however, and consider the calendar and its complexity within its historical contexts, we encounter a rich history of science, influenced by politics, religion, and social change over time.

Astronomy in Mesoamerica

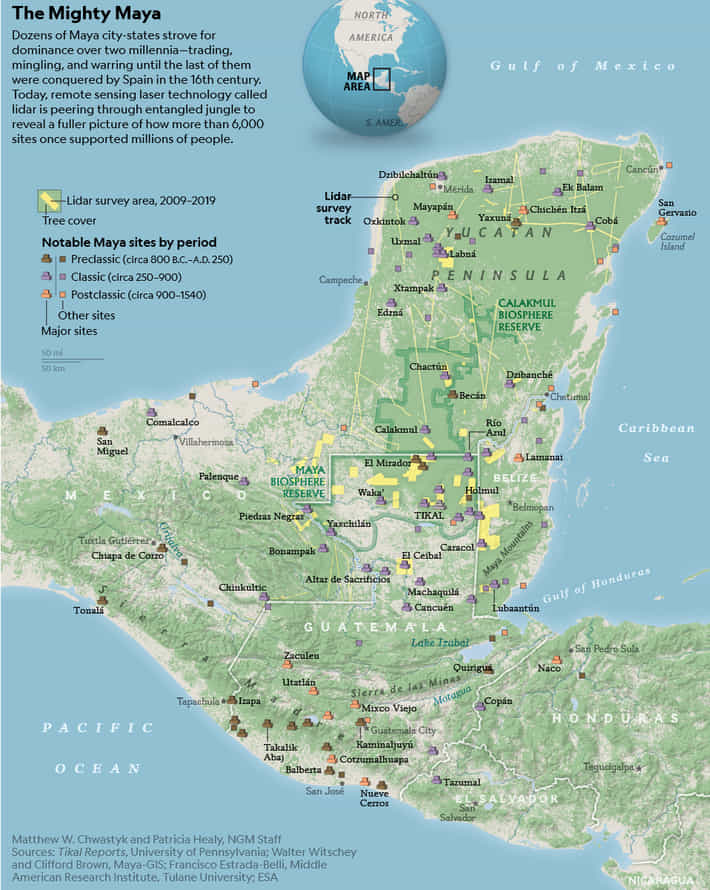

Astronomy in Mesoamerica developed in apparent isolation from the cultural traditions outside of the Americas, and its unique advancement provides an important comparison with parallel developments of astronomical science elsewhere in the world. Containing hundreds of distinct ethnic groups and indigenous languages, the Mesoamerican culture area extends south from central Mexico into Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. While highly diverse, many of the cultures and language groups in this region share innovations such as intensive maize agriculture, stratified urban development, megalithic architecture, and an elaborate calendrical system consisting of a unique, repeating cycle of 260 days, and a cycle of 365 days that estimates the length of the year. Together, these cycles combine to form the 52-year Calendar Round, historically shared by more than fifty linguistic groups in Mesoamerica.

Notes on the Correlation of Maya and Gregorian Calendars

In the 1722 K’iche’ Calendar A there are a number of calendar-round dates that are correlated with Gregorian dates. These dates provide a significant and hitherto unexamined argument in support of the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson (GMT) correlation (correlation constant = 584,283 days) of the Maya and European calendars (Thompson 1935). This paper by Christian Prager and Frauke Sachse was originally published as Appendix 2 in: Weeks, John M., Frauke Sachse and Christian M. Prager: Three Calendars from Highland Guatemala. 221 pp. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2009, pp. 176 – 184. This is the MANUSCRIPT version, for citation please refer to the book version. Prager, Christian M., and Frauke Sachse (2009) Notes on the Correlation of Maya and Gregorian Calendars. In: John M. Weeks, Frauke Sachse and Christian M. Prager (eds.), Maya Daykeeping: Three Calendars from Highland Guatemala; pp. 176 – 184. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

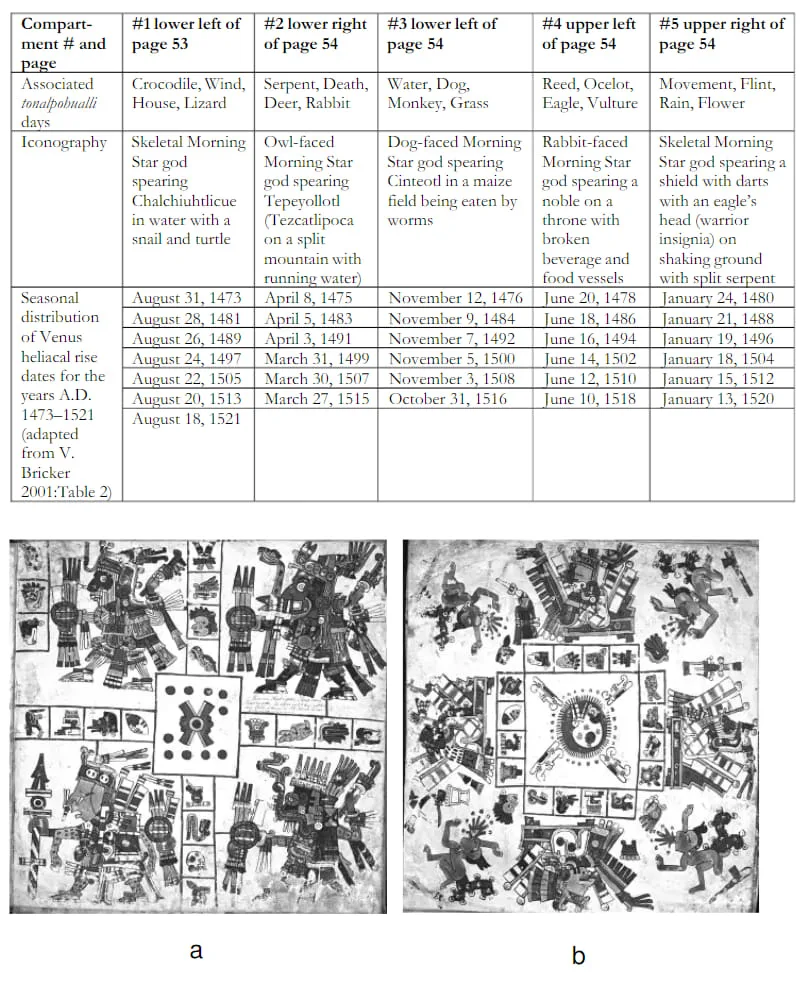

Using Astronomical Imagery to Cross-Date an Almanac in the Borgia Codex

In a 1992 article, V. Bricker and H. Bricker detail their historical approach to dating and decoding codical almanacs in the Maya codices that lack explicit Long Count dates. Astronomical and seasonal imagery are the key to their methodology. In honor of their work, I apply their method to an almanac in the highland Mexican Borgia Codex. After a discussion of Venus iconography identified in the Maya and Borgia Group codices, I discuss how similar astronomical imagery in the almanac on Borgia 49a-52a, 53b can be used to propose a model that situates the instrument in real time.

A Commentary to Christine Hernández’s astronomical interpretation of Skybearer Almanac in Borgia 49a-52a

In her paper “Using Astronomical Imagery to Cross Date an Almanac in the Borgia Codex”Hernández (2006:126) attempts to “place the skybearer almanac [in Borgia 49a-52a] in realtime” by using iconography and tonal glyphs as references to seasonal or astronomical cycles.She also uses the almanac on B53-B54 for the rst risings of morning Venus, which have beencorrelated by V. Bricker (2001, Table 2) for the years 1473 to 1506. Importantly, the openingdate of this second almanac — 1 Cipactli — is calculated by V. Bricker to be 31 August 1473,whereas the Converter I have developed calculates 1 September 1473 (Gregorian proleptic,see Patrick Encina 2013). Within that 24-hour period morning Venus actually made a heliacalrising. That is perhaps the single event that both the dating system used by the Brickers (theGMT correlation and its variants) and the one published by me (Patrick Encina, 2013) find conciliation. Dates some 140 years earlier — like the ones on B49a and B49b — produce 35days of error with the GMT correlation, and so are unable to capture the astronomical event.Dates some 20 years later have 5 days of error with the GMT correlation. The error of theGMT is its miscalculation for leap days. My correlation does not accumulate such a leap-dayrelated error and so recovers the actual astronomical event on any Long Count or CalendarRound date.

Everything we thought we knew about the ancient Maya is being upended

The world the Maya made has been shrouded by jungle for centuries. Now, a tool called lidar is revealing its staggering scale and sophistication.

The two archaeologists, both National Geographic Explorers with research posts at Tulane University, had collectively spent decades working in the jungles of Central America. Grueling heat and humidity, as well as encounters with deadly wildlife and armed looters, were inextricably part of discovering the treasures of the ancient Maya, a civilization that flourished for thousands of years and then mysteriously vanished beneath the dense forest. And so, it seemed ironic — almost unfair — that their biggest discovery would come while huddling around a computer in an air-conditioned office in New Orleans. While his colleague Francisco Estrada-Belli looked on, Marcello Canuto opened an aerial image of a tract of forest in northern Guatemala. At first, the screen showed nothing but treetops. But this image had been made with a technology called lidar (short for “light detection and ranging”). Lidar devices mounted on aircraft shoot billions of laser bursts downward and then measure the ones that reflect back. The small fraction of pulses that penetrate the foliage provide enough data points to assemble an image of the jungle floor.

Keine Kommentare