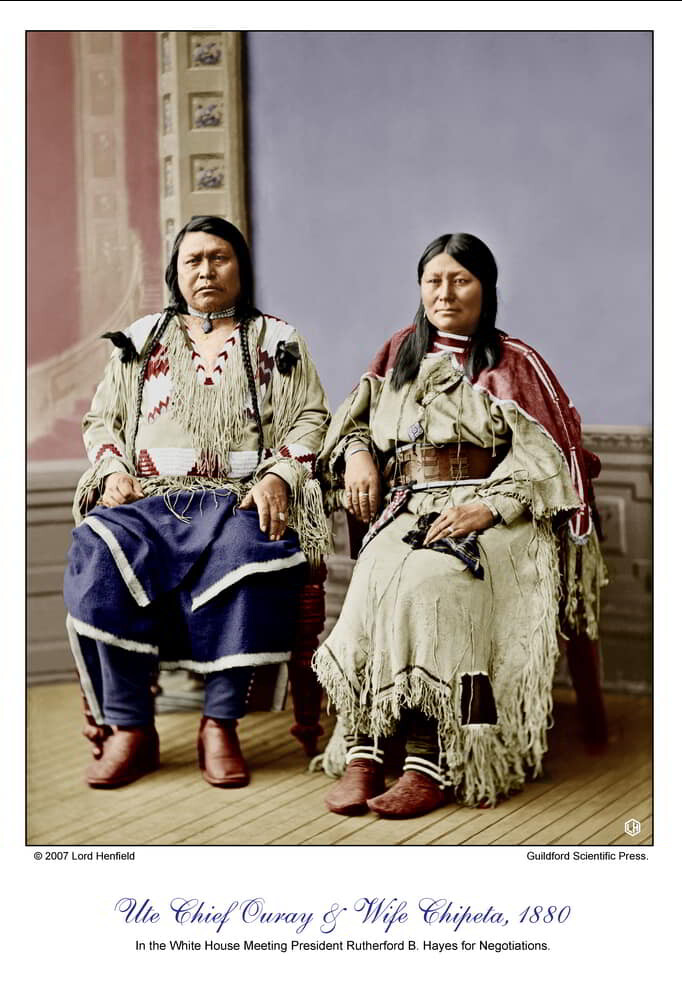

Ute Chief Ouray & Wife Chipeta

INFORMATION ON COLOURISATION

Colourisation [International British English] or colorization [North American English], is any process that adds colour to black-and-white, sepia (brown tone), or other monochrome photographic images. It is also called hand-colouring or colour transforming of photographs and it refers to any method of manually adding colour to a monochrome photograph, generally either to heighten the realism of the image or for artistic purposes. The first examples date from the late 19th century, but colourisation has become common with the advent of digital image processing.

Typically, watercolours, oils, crayons or pastels, and other paints or dyes are applied to the image surface using brushes, fingers, cotton swabs or airbrushes. Hand-coloured photographs were most popular in the mid- to late-19th century before the invention of colour photography and some firms specialised in producing hand-coloured photographs. An early form of colourisation mass production is known as Photochrom (Fotochrom, Photochrome) which is a process for producing colourised images from a single black-and-white photographic negative via the direct photographic transfer of the negative onto lithographic printing plates. The process is a photographic variant of chromolithography (colour lithography). Because no colour information was preserved in the photographic process, the photographer would make detailed notes on the colours within the scene and use the notes to hand paint the negative before transferring the image through coloured gels onto the printing plates.

Monochrome (black and white) photography was first exemplified by the daguerreotype in 1839 and later improved by other methods including: calotype, ambrotype, tintype, albumen print and gelatin silver print. The majority of photography remained monochrome until the mid-20th century.

The so-called golden age of hand-coloured photography in the western hemisphere occurred between 1900 and 1940. The increased demand for hand-coloured landscape photography at the beginning of the 20th century is attributed to the work of Wallace Nutting. Nutting, a New England minister, pursued hand-coloured landscape photography as a hobby until 1904, when he opened a professional studio. He spent the next 35 years creating hand-coloured photographs, and became the best-selling hand-coloured photographer of all time.

By the 1950s, the availability of colour film all but stopped the production of hand-coloured photographs. In spite of the availability of high-quality colour processes, hand-coloured photographs (often combined with sepia toning) are still popular for aesthetic reasons and because the pigments used have great permanence. In many countries where colour film was rare or expensive, or where colour processing was unavailable, hand-colouring continued to be used and sometimes preferred into the 1980s. More recently, digital image processing has been used – particularly in advertising – to recreate the appearance and effects of hand-colouring. Colourisation is now available to the photographer using image manipulation software such as Adobe Photoshop, Corel Draw or Gimp.

Digital photograph restoration

The conservation and restoration of photographs is a new branch of photography in which the physical care and treatment of photographic materials becomes significant to historians. It covers both efforts undertaken by photograph conservators, librarians, archivists, and museum curators who manage photograph collections at a variety of cultural heritage institutions, as well as steps taken to preserve collections of personal and family photographs.

Photograph preservation is distinguished from digital or optical restoration, which is concerned with creating and editing a digital copy of the original image rather than treating the original photographic material. Digital photograph restoration is the practice of restoring the appearance of a digital copy of a physical photograph which has been damaged by natural, man-made, or environmental causes or simply affected by age or neglect.

Digital photograph restoration uses a variety of image editing techniques to remove visible damage and aging effects from digital copies of physical photographs. Raster graphics editors are typically used to repair the appearance of the digital images and add to the digital copy to replace torn or missing pieces of the physical photograph. Evidence of dirt, and scratches, and other signs of photographic age are removed from the digital image manually, by painting over them meticulously. Unwanted colour casts are removed and the image’s contrast or sharpening may be altered in an attempt to restore some of the contrast range or detail that is believed to have been in the original physical image. Image processing techniques such as image enhancement and image restoration are also applicable for the purpose of digital photograph restoration.

History was never just grey, as monochrome photographs may suggest, but colourful and vivid. As black-and-white photographs display only a limited range of three-dimensional depth by lack of colour, added information by colourisation can contribute to education of history. This information is usually retrieved from written physical descriptions, from paintings, from displays of items and clothes in museums, and to some extent from the grey tones of the photograph itself. Although the colourisation of photographs and films is therefore an expression of art, it can bring a bygone age closer to the spectator than just reading about it ever could do.

Henfield and Photography

Due to his studies of archaeological and historical documents, Henfield worked as photographer and in a photo lab as well. During this time, he found out how to turn monochrome photographs into colour photographs. Lord Henfield’s colourised photographs imitate the chemical structures of colour negatives on Celluloid film in an electronic way. Henfield has chosen the material of Mathew Brady for the simple reason that the quality of Brady’s photographs is so crisp, sharp, and clear that it has surpassed the photo quality of any other photographer for almost 100 years.

MATHEW B. BRADY

Mathew Benjamin Brady (c. 1822 – 1824 – January 15, 1896) was one of the earliest photographers in American history. Best known for his scenes of the Civil War, he studied under inventor Samuel F. B. Morse, who pioneered the daguerreotype technique in America. Brady opened his own studio in New York City in 1844, and photographed Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and Abraham Lincoln, among other public figures.

When the Civil War started, his use of a mobile studio and darkroom enabled vivid battlefield photographs that brought home the reality of war to the public. Thousands of war scenes were captured, as well as portraits of generals and politicians on both sides of the conflict, though many of these were taken by his assistants, rather than by Brady himself. After the war, these pictures went out of fashion, and the government did not purchase the master-copies as he had anticipated. Brady’s fortunes declined sharply, and he died in debt.

His Life

Brady left little record of his life before photography. Speaking to the press in the last years of his life, he stated that he was born between 1822 and 1824 in Warren County, New York, near Lake George. He was the youngest of three children to Irish immigrant parents, Andrew and Samantha Julia Brady. In official documents before and during the war, however, he claimed to have been born himself in Ireland.At age 16, Brady moved to Saratoga, New York, where he met portrait painter William Page and became Page’s student. In 1839, the two traveled to Albany, New York, and then to New York City, where Brady continued to study painting with Page, and also with Page’s former teacher, Samuel F. B. Morse. Morse had met Louis Jacques Daguerre in France in 1839, and returned to the US to enthusiastically push the new daguerreotype invention of capturing images. At first, Brady’s involvement was limited to manufacturing leather cases that held daguerreotypes. But soon he became the centre of the New York artistic colony that wished to study photography. Morse opened a studio and offered classes; Brady was one of the first students.

In 1844, Brady opened his own photography studio at the corner of Broadway and Fulton Street in New York, and by 1845, he began to exhibit his portraits of famous Americans, including the likes of Senator Daniel Webster and poet Edgar Allan Poe. In 1849, he opened a studio at 625 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., where he met Juliet Handy (often just called ‘Julia’), whom he married in 1850 and lived with on Staten Island. Brady’s early images were daguerreotypes, and he won many awards for his work; in the 1850s ambrotype photography became popular, which gave way to the albumen print, a paper photograph produced from large glass negatives most commonly used in the American Civil War photography.

In 1850, Brady produced The Gallery of Illustrious Americans, a portrait collection of prominent contemporary figures. The album, which featured noteworthy images including the elderly Andrew Jackson at the Hermitage, was not financially rewarding but invited increased attention to Brady’s work and artistry. In 1854, Parisian photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri popularised the carte de visite and these small pictures (the size of a visiting card) rapidly became a popular novelty; thousands were created and sold in the United States and Europe.

In 1856, Brady placed an ad in the New York Herald offering to produce “photographs, ambrotypes and daguerreotypes.” This inventive ad pioneered, in the US, the use of typeface and fonts that were distinct from the text of the publication and from that of other advertisements.

Civil War documentation

At first, the effect of the Civil War on Brady’s business was a brisk increase in sales of cartes de visite to departing soldiers. Brady readily marketed to parents the idea of capturing their young soldiers’ images before they might be lost to war by running an ad in The New York Daily Tribune that warned, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.” However, he was soon taken with the idea of documenting the war itself. He first applied to an old friend, General Winfield Scott, for permission to have his photographers travel to the battle sites, and eventually, he made his application to President Lincoln himself. Lincoln granted permission in 1861, with the proviso that Brady finance the project himself.

His efforts to document the American Civil War on a grand scale by bringing his photographic studio onto the battlefields earned Brady his place in history. Despite the dangers, financial risk, and discouragement by his friends, Brady was later quoted as saying “I had to go. A spirit in my feet said ‘Go,’ and I went.” His first popular photographs of the conflict were at the First Battle of Bull Run, in which he got so close to the action that he barely avoided capture. While most of the time the battle had ceased before pictures were taken, Brady came under direct fire at the First Battle of Bull Run, Petersburg, and Fredericksburg.

He also employed Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, William Pywell, George N. Barnard, Thomas C. Roche, and seventeen other men, each of whom was given a traveling darkroom, to go out and photograph scenes from the Civil War. Brady generally stayed in Washington, D.C., organizing his assistants and rarely visited battlefields personally. However, as author Roy Meredith points out, “He [Brady] was essentially the director. The actual operation of the camera though mechanical is important, but the selection of the scene to be photographed is as important, if not more so than just ’snapping the shutter.’ ”

This may have been due, at least in part, to the fact that Brady’s eyesight had begun to deteriorate in the 1850s. Many of the images in Brady’s collection are, in reality, thought to be the work of his assistants. Brady was criticised for failing to document the work, though it is unclear whether it was intentional or due simply to a lack of inclination to document the photographer of a specific image. Because so much of Brady’s photography is missing information, it is difficult to know not only who took the picture, but also exactly when or where it was taken.

In October 1862 Brady opened an exhibition of photographs from the Battle of Antietam in his New York gallery, titled The Dead of Antietam. Many images in this presentation were graphic photographs of corpses, a presentation new to America. This was the first time that many Americans saw the realities of war in photographs, as distinct from previous “artists’ impressions”.

Mathew Brady, through his many paid assistants, took thousands of photos of American Civil War scenes. Much of the popular understanding of the Civil War comes from these photos. There are thousands of photos in the US National Archives and the Library of Congress taken by Brady and his associates, Alexander Gardner, George Barnard and Timothy O’Sullivan. The photographs include Lincoln, Grant, and soldiers in camps and battlefields. The images provide a pictorial cross reference of American Civil War history. Brady was not able to photograph actual battle scenes, as the photographic equipment in those days was still in the infancy of its technical development and required that a subject be still for a clear photo to be produced.

Following the conflict, a war-weary public lost interest in seeing photos of the war, and Brady’s popularity and practice declined drastically.

Later years

During the war, Brady spent over $100,000 (equivalent to $1,691,000 in 2020) to create over 10,000 plates. He expected the US government to buy the photographs when the war ended. When the government refused to do so he was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy. Congress granted Brady $25,000 in 1875, but he remained deeply in debt. The public was unwilling to dwell on the gruesomeness of the war after it had ended, and so private collectors were scarce.

Depressed by his financial situation and loss of eyesight, and devastated by the death of his wife in 1887, he died penniless in the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York City on January 15, 1896, from complications following a streetcar accident. Brady’s funeral was financed by veterans of the 7th New York Infantry. He was buried in the Congressional Cemetery, which is located in Barney Circle, a neighbourhood in the Southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C.

Brady’s Legacy

Brady photographed 18 of the 19 American presidents from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley. The exception was the 9th President, William Henry Harrison, who died in office three years before Brady started his photographic collection. Brady photographed Abraham Lincoln on many occasions. His Lincoln photographs have been used for the $5 bill, on the Lincoln penny and on the 90c Lincoln Postage stamp issue of 1869.

The thousands of photographs which Mathew Brady’s photographers (such as Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan) took have become the most important visual documentation of the Civil War, and have helped historians and the public better understand the era. The historian Lord Henfield has used several dozen of them for colourisation. Many hundreds of them were used by Ken Burns in his 9‑episode documentary TV and video series The Civil War. Thousands of Brady’s photographs are accessible and now available for download as tiff-files from the website of the Libraray of Congress.

Brady photographed and made portraits of many senior Union officers in the war, including:

• Ulysses S. Grant• Nathaniel Banks• Don Carlos Buell• Ambrose Burnside• Benjamin Butler• Joshua Chamberlain• George Custer• David Farragut• John Gibbon• Winfield Hancock• Samuel P. Heintzelman• Joseph Hooker• Oliver Otis Howard• David Hunter• John A. Logan• Irvin McDowell• George McClellan• James McPherson• George Meade• Montgomery C. Meigs• David Dixon Porter• William Rosecrans• John Schofield• William Sherman• Daniel Sickles• Henry Warner Slocum• George Stoneman• Edwin V. Sumner• George Thomas• Emory Upton• James Wadsworth• Lew WallaceOn the Confederate side, Brady photographed:• Jefferson Davis• Robert E. Lee• P. G. T. Beauregard• Stonewall Jackson• Albert Pike• James Longstreet• James Henry Hammond• Henry Hopkins Sibley

Brady also photographed thousands of other perple, from Lord Lyons, the British ambassador to Washington during the Civil War, to Pedro II, emperor of Brazil.

Photojournalism and honours

Brady is credited with being the father of photojournalism.[19] He can also be considered a pioneer in the orchestration of a “corporate credit line.” In this practice, every image produced in his gallery was labeled “Photo by Brady”; however, Brady dealt directly with only the most distinguished subjects and most portrait sessions were carried out by others.

As perhaps the best-known US photographer in the 19th century, it was Brady’s name that came to be attached to the era’s heavy specialised end tables which were factory-made specifically for use by portrait photographers. Such a “Brady stand” of the mid-19th century typically had a weighty cast iron base for stability, plus an adjustable-height single-column pipe leg for dual use as either a portrait model’s armrest or (when fully extended and fitted with a brace attachment rather than the usual tabletop) as a neck rest. The latter was often needed to keep models steady during the longer exposure times of early photography. While Brady stand is a convenient term for these trade-specific articles of studio equipment, there is no proven connection between Brady himself and the Brady stand’s invention circa 1855.

In 2013, Brady Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was officially renamed “Mathew Brady Street.” The original namesake Brady was W. Tate Brady, a prominent businessman in Tulsa’s early history, who had connexions to the Ku Klux Klan and other racist organisations. Following considerable controversy, the City Council of Tulsa, OK on August 15, 2013, voted to retain the name Brady for the street, but that it would now refer to and honor Mathew B. Brady instead. Mathew Brady never visited Tulsa in his lifetime.

Books and documentaries

Brady and his Studio produced over 7,000 pictures (mostly two negatives of each). One set “after undergoing extraordinary vicissitudes,” came into U.S. government possession. His own negatives passed in the 1870s to E. & H. T. Anthony & Company of New York, in default of payment for photographic supplies. They “were kicked about from pillar to post” for 10 years, until John C. Taylor found them in an attic and bought them; from this they became “the backbone of the Ordway – Rand collection; and in 1895 Brady himself had no idea of what had become of them. Many were broken, lost, or destroyed by fire. After passing to various other owners, they were discovered and appreciated by Edward Bailey Eaton,” who set in motion “events that led to their importance as the nucleus of a collection of Civil War photos published in 1912 as The Photographic History of the Civil War.

Some of the lost images are mentioned in the last episode of Ken Burns’ 1990 documentary on the Civil War. Burns claims that glass plate negatives were often sold to gardeners, not for their images, but for the glass itself to be used in greenhouses and cold frames. In the years that followed the end of the war, the sun slowly burned away their filmy images and they were lost.

Exhibitions

On September 19, 1862, two days after the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest day of combat on U.S. soil with more than 23,000 killed, wounded or missing, Mathew Brady sent photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson to photograph the carnage. In October 1862, Brady displayed the photos by Gardner at Brady’s New York gallery under the title “The Dead of Antietam.” The New York Times published a review. In October 2012, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine displayed 21 original Mathew Brady photographs from 1862 documenting the Civil War’s Battle of Antietam.

ADDITIONAL TEXT BY YALE UNIVERSITY

Mathew B. Brady and Levin Corbin Handy Photographic Studios CollectionCollection Call Number: GEN MSS 580

Overview

Photographs, papers, and artifacts created or collected by Mathew B. Brady, Levin Corbin handy, their studios, and their family, 1843 – 1957. The collection includes images created by Brady during the American Civil War and documents the continual use of these images into the early twentieth century by Handy and his studio. The collection reflects the operations of the Brady and Handy studios in Washington, D.C., from the middle of the nineteenth century through the early twentieth century. It contains work by other photographers and other studios collected by Handy, as well as camera lenses and other photographic artifacts. A small group of papers document aspects of the extended Handy family history.

Mathew B. Brady (circa 1823 – 1896)

Mathew B. [Benjamin] Brady (circa 1823 – 1896) was an American photographer who achieved prominence through his portrait photographs and his organization of photographers to document the American Civil War from his studio in Washington, D.C.

Born in Warren County, New York, to Irish immigrant parents, Brady learned the daguerreotype process in Saratoga, New York. By 1844, he operated a daguerreotype studio in New York, New York. The following year he established his gallery of illustrious Americans, which consisted of daguerreotype portraits of American celebrities, he published a portion as lithographic reproductions in 1850.

In 1849, Brady established a studio in Washington D.C., with the expectation of creating portraits of senators and congressional representatives, but he closed it within a year due to high operating expenses and local competition. While in Washington, he met Juliette Handy, whom he married two years later. Around this time, Brady’s eyesight began to fail and he concentrated on the management of his studios, which included posing sitters for their portraits, while employees created the photographs. In 1853, he opened a second studio in New York, New York.

In 1858, Brady re-established a studio in Washington D.C., with Alexander Gardner as his primary photographer. With the onset of the American Civil War, Brady organized a corps of photographers and assistants to document the people, events, and locales of the war. Photographers in this group included George N. Barnard, Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, William Pywell, and Thomas C. Roche. The photographers created conventional portraits of individuals and groups, views of military encampments, and the aftermath of battles. Images published or adapted as engravings in publications had the credit “Photograph by Brady.

Brady sought to market images of the American Civil War with little success. During the war, he transferred many original glass plate negatives to the photographic supply firm of E. & H. T. Anthony & Company to settle his debts with the company. In 1942, the Library of Congress purchased much of this material, where it became the Anthony-Taylor-Rand-Ordway-Eaton Collection.

Brady spent an estimated $100,000 to print ten thousand photographic prints documenting the American Civil War, but a lack of customers required him to sell his studios in New York and Washington and declare bankruptcy. In 1875, he finally sold a bulk of his photographs to the United States government for $25,000. Much of this material became part of the files of the Department of War eventually deposited in the United States National Archives and Records Administration. Nevertheless, Brady remained deeply in debt.By 1883, Brady formed a photographic partnership with his nephew, Levin Corbin Handy, and Samuel C. Chester, to market images from the American Civil War and maintain a photographic studio in Washington. In 1887, Juliette Handy Brady died. Brady continued to face financial difficulties through the remainder of his life. On January 15, 1896, Brady died in the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York, New York, from complications following a streetcar accident. After his death, his remaining photography files became the property of Levin Corbin Handy.

Levin Corbin Handy

Levin Corbin Handy (1855 – 1932), an American photographer, was a nephew and former apprentice of Mathew B. Brady. Born in Washington, D.C., the son of Samuel S. Handy and Mary A. Handy, Handy began working in the Brady studio as an apprentice in 1867. He soon demonstrated himself as a skilled camera operator, and established his own photographic business in Washington by 1871.

Around 1880, Handy entered a photographic partnership with Samuel C. Chester. They operated a studio in Cape May, New Jersey in 1882. By 1883, Handy and Chester partnered with Brady to market images from the American Civil War. Chester ultimately left the partnership, while Handy maintained the studio at his home and studio located at 494 Maryland Avenue Southwest, Washington, D.C. When Mathew B. Brady died in 1896, his remaining photography files became the property of Handy.

In Washington, the L.C. Handy Studio offered an array of traditional photographic services, in particular to the Library of Congress and other governmental agencies. He also provided photograph duplication services to patrons of the Library of Congress and to members of the United States Congress.

Handy died at his home on March 23, 1932. He bequeathed his studio and photographic files, including his collection of Mathew B. Brady, to his daughters, Alice H. Cox and Mary H. Evans. In 1954, the Library of Congress purchased approximately ten thousand original, duplicate, and copy negatives from Cox and Evans.

Processing Information

Upon acquisition, the Mathew B. Brady and Levin Corbin Handy Photographic Studios Collection had no discernible order and many items had damage or soiling. A group of flexible photographic negatives were discarded due to severe deterioration.

The processing archivist did not distinguish the rank of military officers and soldiers in the photographic imagery, nor establish individual photographers or dates of images.

In April 2015, library staff revised the finding aid to reflect the storage of photographic material on broken glass carriers, as well as correcting typographical errors.

COLLECTION

Scope and Contents

This collection consists primarily of photographs created by the studios of Mathew B. Brady and his nephew and former apprentice, Levin Corbin Handy, in Washington, D.C.

The collection includes imagery created by photographers employed by Brady during the American Civil War and documents his marketing of that imagery, as well as the continuing efforts of the Levin C. Handy Studio to promote and market this wartime imagery into the early twentieth century. The collection also documents the functioning of photographic studios in Washington, D.C., from the middle of the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, and the personal photography and papers of the Handy family. The collection includes the work of other photographers and photographic studios collected by Handy, as well as artifacts related to photography.

This collection largely represents photographic material retained by Handy’s daughters. Other photographic materials created by Brady and his studios were transferred to creditors during the American Civil War, purchased by the United States government in 1875, or purchased by Library of Congress in 1954. At the time of processing this collection, many of the images created by the Brady studio were available in digital form from the United States National Archives and Records Administration and the Library of Congress via the Internet.

Each folder in the collection contains a single photographic print, except where two or more photographic prints are noted, and each sleeve contains a single photographic negative, except where two or more film negatives are noted.

Dates: 1843 — 1957; Majority of material found within 1860 — 1935

Creator: Brady, Matthew B. [Benjamin], approximately 1823 – 1896

Conditions Governing Access

The materials are open for research.

Conditions Governing Use

The Mathew B. Brady and Levin Corbin Handy Photographic Studios Collection is the physical property of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. For further information, consult the appropriate curator.

Immediate Source of Acquisition

Purchased from the William Reese Company on the Edwin J. Beinecke Book Fund, 2006.

Arrangement

Organized into four series: I. Mathew B. Brady Studio. II. Levin Corbin Handy Studio. III. Family Papers and Photographs. IV. Collected Photographs and Artifacts.

Within each series, the photographic materials are arranged according to format and presentation.

Extent

28.44 Linear Feet (76 boxes)

Language of Materials

English

Catalog Record

A record for this collection is available in Orbis, the Yale University Library catalog

Persistent URL

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/brhc/

http://hdl.handle.net/10079/fa/beinecke.bradyhandy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_photography

Keine Kommentare